By Valery FADEEV (Russia)

For the average person, the term “Byzantium” evokes a number of negative associations: Eastern despotism, political intrigues, backwardness, etc. These memes are firmly rooted in public opinion, in the guise of proven historical facts. However, this generally accepted image of Byzantium,is, in fact, a fabricated one, that has been thrust into the public arena. But no secret plot or conspiracy was responsible for this. The “scholarly” history of Byzantium is a vivid, perhaps even the most vivid example of how ideology can distort the study of human history.

The primary suppositions about Byzantine historiography were presented almost two centuries ago by the British historian Edward Gibbon in his multi-volume work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in which Gibbon first described Rome itself before its fall in the year 476, and then included Byzantium in the scope of his research, ending his description with its own fall in 1453. Gibbon sums up the history of the Byzantine Empire, viewing it as an amalgamation of blemishes and intrigues, a symbol of historic stagnation, and a betrayal of the ideals of Antiquity. Edward Gibbon established the tradition of how to interpret the history of Byzantium, and his views held sway over scholars of history around the world for many years.

As a result, the contemporary historian John Norwich had to admit in his book Byzantium (I): The Early Centuries: “During my five years at one of England’s oldest and finest public schools, Byzantium seems to have been the victim of a conspiracy of silence. I cannot honestly remember its being mentioned, far less studied … Many people, I suspect, feel similarly vague today …”

The Truth About Byzantium

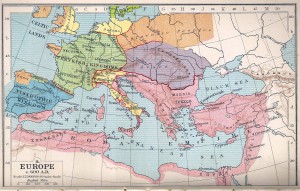

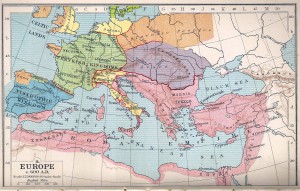

Eastern Roman Empire at 600 AD

Once we reject the British propaganda, let us take an honest look at what Byzantium actually was.

Let’s start with the fact that that wasn’t its name. Western historians introduced the term “Byzantine Empire” only long after the state in question had ceased to exist. It had previously been known as the Eastern Roman Empire, and the inhabitants of the empire continued to refer to themselves as Romans. In Greek, Romans are known as “Romioi,” from which we derive another version of its name: the Romaion Empire. Obviously the new designation was coined to emphasize the differences – religious, cultural, and civilizational – between Byzantium and Rome, between classical Antiquity and the history of the West in general, in order to in some way juxtapose the “progressive West” against the “archaic East.”

Peter Paul Rubens: “Constantine directing the building of Constantinople” (painted around 1624)

The empire was founded by the Roman Emperor Constantine in 330 AD. After winning power, Constantine, intending to make Christianity the state religion, took a radical step – he moved the capital farther from the convulsive and unending civil wars of pagan Rome, taking it eastward to the small city of Byzantium, which he named New Rome. Thus began the history of the Byzantine Empire, lasting over a thousand years.

Geographically, the new state took possession of the eastern domains of the Roman Empire, and subsequently the western realms buckled under the attacks of the barbarians. In the sixth century, Emperor Justinian even managed to briefly retake some of the lost Roman lands – all of Italy, northern Africa, and the southern Iberian Peninsula. This was the high point for Byzantium’s territorial expansion.

For many centuries the Mediterranean dominated the empire’s economic and trade relations. There was no good that was not produced or could not be purchased within the empire. It is believed that at its height, the empire generated up to 90% of all the products used in Eurasia west of India. But a marked economic decline occurred in the 12th and 13th centuries under pressure from Venice and Genoa.

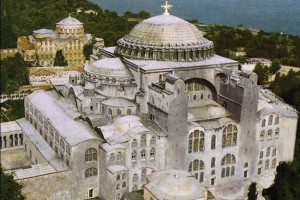

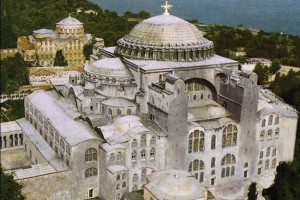

Hagia Sophia Cathedral, built in 537, reconstuction picture

Constantinople was the greatest city of the Middle Ages. It is estimated that in the seventh century its population reached 700,000. (At that time the population of Paris was no more than 15,000). Many more centuries would pass before any European city could be compared to Constantinople. The majestic Hagia Sophia Cathedral, built in 537, was the world’s largest Christian church until 1626, when St. Peter’s Basilica was consecrated in Rome. In other words, it took over a thousand years for anyone to surpass the Byzantines in the art of construction. The city was filled with palaces, churches, the villas of the rich, and works of art. When the Crusaders captured Constantinople in 1204, thousands of marauders returned home wealthy men, after many days of plunder. During that time, many works of art, some ancient, were destroyed, and the Crusaders’ deportment differed little from that seen during the barbaric looting of Rome almost a millennium earlier.

Traces of this massive thievery are still visible today e.g. in Venice. St. Mark’s Basilica, the biggest tourist attraction in that magnificent city, was built in the ninth century in an austere Romanesque style (there was no other in the West at that time). But the cathedral’s exterior appearance changed dramatically after the crusade of 1204 – it was adorned with the columns and capitals of Byzantine palaces. The famous Triumphal Quadriga of horses, the work of the great classical sculptor Lysippos, can be seen on the cathedral’s balcony. The Quadriga was also seized from Constantinople, although there the sculpture of horses stood, as one would expect, at the hippodrome. For some reason the Venetians erected them in a Christian church, clearly enormously proud of their spoils of war.

The Quadriga of horses, by the classical sculptor Lysippos, on the balcony of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.They were carted off from Constantinople after the plunder of 1204.

However it was not these extraordinary feats achieved by the empire – its wealth, trade, the erection of cities and extraordinary churches, art, and diplomacy – that define Byzantium’s role in human history, although this is not a bad list and certainly worth a bit of attention in history books. Emperor Constantine fulfilled his dream of declaring Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. It was this decision that was to determine the fate of all of western Eurasia in the coming centuries.

Constantine chose to take this step at a time when Christianity was already widespread throughout the Roman Empire. However, due to its incompatibility with pagan beliefs, the truly underground nature of this new faith often resulted in Christians being cruelly persecuted. But the steady stream of converts, which included high-ranking officials, military officers, and the rich, as well as simple folk, was so great that that it was not possible to entirely stifle and repress this new religion. As it emerged from the underground, Romans adopted the new faith en masse, and a rapid shift was seen from paganism to Christianity.

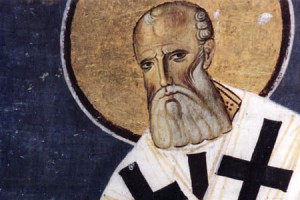

Gregory the Theologian. An icon written in Serbia in 1204.

Christian theology blossomed. The classical tradition of debate found new ground, with the addition of a powerful intellectual barrage. Take, for example,Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom – three great saints and Christian students ofAthanasius the Great and John of Damascus, one of whose followers became Thomas Aquinas, the great Latin theologian and the author of theSumma Theologica. These distinguished thinkers provided the underlying theological basis for the new world.

It is important to note that within what was now a Christian empire, the classical world continued to exist. It was simply a part of everyday life, like the sculptures of the horses at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, and yes, in fact, like the hippodrome itself, as something to be used for mass entertainment. Nor was classical thinking forbidden: Plato’s Academy, for example, was not closed until 529. Classical thinking was not forbidden, it merely became obsolete and was supplanted by a new philosophy – Christian.

And so, let us sum up our interim conclusions. It is simply not true that the Roman Empire was destroyed under the onslaught of the barbarians, leading to the onset of the “Dark Ages.”The western part of the empire lay in ruins, but its eastern expanses flourished. There were no “Dark Ages” in the East. On the contrary, there one could find a great empire, unequaled by any.

Logo: the fragment of a Byzantine icon from St.Catherine’s monastery, Sinai, VI century AD.

Valery Fadeev is the Editor-in-Chief of the Russian leading political journal EXPERT. He is a member of Civic Chamber of Russia and Supreme Council of the ruling United Russia political party. The publication is based on his article “On a solid basement” published in Russian in the latest edition of EXPERT.

The primary suppositions about Byzantine historiography were presented almost two centuries ago by the British historian Edward Gibbon in his multi-volume work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in which Gibbon first described Rome itself before its fall in the year 476, and then included Byzantium in the scope of his research, ending his description with its own fall in 1453. Gibbon sums up the history of the Byzantine Empire, viewing it as an amalgamation of blemishes and intrigues, a symbol of historic stagnation, and a betrayal of the ideals of Antiquity. Edward Gibbon established the tradition of how to interpret the history of Byzantium, and his views held sway over scholars of history around the world for many years.

As a result, the contemporary historian John Norwich had to admit in his book Byzantium (I): The Early Centuries: “During my five years at one of England’s oldest and finest public schools, Byzantium seems to have been the victim of a conspiracy of silence. I cannot honestly remember its being mentioned, far less studied … Many people, I suspect, feel similarly vague today …”

The Truth About Byzantium

Eastern Roman Empire at 600 AD

Once we reject the British propaganda, let us take an honest look at what Byzantium actually was.

Let’s start with the fact that that wasn’t its name. Western historians introduced the term “Byzantine Empire” only long after the state in question had ceased to exist. It had previously been known as the Eastern Roman Empire, and the inhabitants of the empire continued to refer to themselves as Romans. In Greek, Romans are known as “Romioi,” from which we derive another version of its name: the Romaion Empire. Obviously the new designation was coined to emphasize the differences – religious, cultural, and civilizational – between Byzantium and Rome, between classical Antiquity and the history of the West in general, in order to in some way juxtapose the “progressive West” against the “archaic East.”

Peter Paul Rubens: “Constantine directing the building of Constantinople” (painted around 1624)

The empire was founded by the Roman Emperor Constantine in 330 AD. After winning power, Constantine, intending to make Christianity the state religion, took a radical step – he moved the capital farther from the convulsive and unending civil wars of pagan Rome, taking it eastward to the small city of Byzantium, which he named New Rome. Thus began the history of the Byzantine Empire, lasting over a thousand years.

Geographically, the new state took possession of the eastern domains of the Roman Empire, and subsequently the western realms buckled under the attacks of the barbarians. In the sixth century, Emperor Justinian even managed to briefly retake some of the lost Roman lands – all of Italy, northern Africa, and the southern Iberian Peninsula. This was the high point for Byzantium’s territorial expansion.

For many centuries the Mediterranean dominated the empire’s economic and trade relations. There was no good that was not produced or could not be purchased within the empire. It is believed that at its height, the empire generated up to 90% of all the products used in Eurasia west of India. But a marked economic decline occurred in the 12th and 13th centuries under pressure from Venice and Genoa.

Hagia Sophia Cathedral, built in 537, reconstuction picture

Constantinople was the greatest city of the Middle Ages. It is estimated that in the seventh century its population reached 700,000. (At that time the population of Paris was no more than 15,000). Many more centuries would pass before any European city could be compared to Constantinople. The majestic Hagia Sophia Cathedral, built in 537, was the world’s largest Christian church until 1626, when St. Peter’s Basilica was consecrated in Rome. In other words, it took over a thousand years for anyone to surpass the Byzantines in the art of construction. The city was filled with palaces, churches, the villas of the rich, and works of art. When the Crusaders captured Constantinople in 1204, thousands of marauders returned home wealthy men, after many days of plunder. During that time, many works of art, some ancient, were destroyed, and the Crusaders’ deportment differed little from that seen during the barbaric looting of Rome almost a millennium earlier.

Traces of this massive thievery are still visible today e.g. in Venice. St. Mark’s Basilica, the biggest tourist attraction in that magnificent city, was built in the ninth century in an austere Romanesque style (there was no other in the West at that time). But the cathedral’s exterior appearance changed dramatically after the crusade of 1204 – it was adorned with the columns and capitals of Byzantine palaces. The famous Triumphal Quadriga of horses, the work of the great classical sculptor Lysippos, can be seen on the cathedral’s balcony. The Quadriga was also seized from Constantinople, although there the sculpture of horses stood, as one would expect, at the hippodrome. For some reason the Venetians erected them in a Christian church, clearly enormously proud of their spoils of war.

The Quadriga of horses, by the classical sculptor Lysippos, on the balcony of St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.They were carted off from Constantinople after the plunder of 1204.

However it was not these extraordinary feats achieved by the empire – its wealth, trade, the erection of cities and extraordinary churches, art, and diplomacy – that define Byzantium’s role in human history, although this is not a bad list and certainly worth a bit of attention in history books. Emperor Constantine fulfilled his dream of declaring Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire. It was this decision that was to determine the fate of all of western Eurasia in the coming centuries.

Constantine chose to take this step at a time when Christianity was already widespread throughout the Roman Empire. However, due to its incompatibility with pagan beliefs, the truly underground nature of this new faith often resulted in Christians being cruelly persecuted. But the steady stream of converts, which included high-ranking officials, military officers, and the rich, as well as simple folk, was so great that that it was not possible to entirely stifle and repress this new religion. As it emerged from the underground, Romans adopted the new faith en masse, and a rapid shift was seen from paganism to Christianity.

Gregory the Theologian. An icon written in Serbia in 1204.

Christian theology blossomed. The classical tradition of debate found new ground, with the addition of a powerful intellectual barrage. Take, for example,Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian, and John Chrysostom – three great saints and Christian students ofAthanasius the Great and John of Damascus, one of whose followers became Thomas Aquinas, the great Latin theologian and the author of theSumma Theologica. These distinguished thinkers provided the underlying theological basis for the new world.

It is important to note that within what was now a Christian empire, the classical world continued to exist. It was simply a part of everyday life, like the sculptures of the horses at the Hippodrome of Constantinople, and yes, in fact, like the hippodrome itself, as something to be used for mass entertainment. Nor was classical thinking forbidden: Plato’s Academy, for example, was not closed until 529. Classical thinking was not forbidden, it merely became obsolete and was supplanted by a new philosophy – Christian.

And so, let us sum up our interim conclusions. It is simply not true that the Roman Empire was destroyed under the onslaught of the barbarians, leading to the onset of the “Dark Ages.”The western part of the empire lay in ruins, but its eastern expanses flourished. There were no “Dark Ages” in the East. On the contrary, there one could find a great empire, unequaled by any.

Logo: the fragment of a Byzantine icon from St.Catherine’s monastery, Sinai, VI century AD.

Valery Fadeev is the Editor-in-Chief of the Russian leading political journal EXPERT. He is a member of Civic Chamber of Russia and Supreme Council of the ruling United Russia political party. The publication is based on his article “On a solid basement” published in Russian in the latest edition of EXPERT.