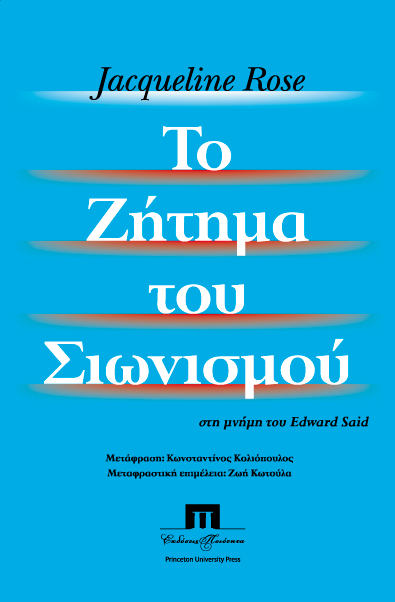

Εισαγωγή ειδικού συνεργάτη. Το Ισραήλ και το Μεσανατολικό ζήτημα που δημιουργήθηκε από την ίδρυση του Εβραϊκού κράτους το 1648 ένα μέγα θέμα που αγγίζει κάθε πτυχή των στρατηγικών εξελίξεων στην περιφέρειά μας. Τις ρίζες του τις εξετάζει η εβραϊκής καταγωγής Καθηγήτρια Jacqueline Rose Το ζήτημα του σιωνισμού (σελίδα facebook) που κυκλοφορήσαμε στα Ελληνικά. Είναι χαρακτηριστικό ότι το αφιέρωσε στον Said, γνωστό Παλαιστίνιο πολιτικό στοχαστή. Το Ισραήλ από κάθε άποψη είναι μια μεγάλη δύναμη. Γύρω από την διένεξη με τους Άραβες μετά το 1948 περιστρέφονται πολλά άλλα. Κυρίως, το Ισραήλ έχει κατορθώσει να ασκεί στρατηγική εποπτεία στην περιφέρεια στην οποία ανήκει, να αμύνεται κατά όποιου απειλεί την επιβίωσή του, να συγκροτεί ρευστές συμμαχίες με εχθρούς και φίλους και κυρίως να αναπτύσσει πελατειακές σχέσεις με τις μεγάλες δυνάμεις οι οποίες ακατάπαυστα αναπτύσσουν στρατηγικές είτε διείσδυσης είτε αντίκρουσης άλλων μεγάλων δυνάμεων που επιδιώκουν παρουσία και έλεγχο των πλουτοπαραγωγικών πόρων. Ταυτόχρονα, κανείς θα πρέπει να λάβει υπόψη ότι η Μέση και Μείζονα Μέση Ανατολή είναι ένα κρίσιμο σημείο της περιμέτρου της Ευρασίας πάνω στην οποία διεξάγονται ανελέητοι ανταγωνισμοί μεταξύ των μεγάλων δυνάμεων τους τελευταίους αιώνες. Για τις ηπειρωτικές δυνάμεις, βασικά την Ρωσία, το ζήτημα είναι να κατέβει στα «θερμά νερά» για να παύσει να είναι μόνο περιφερειακή ηπειρωτική δύναμη και να καταστεί πλανητική δύναμη (Η πρώην Σοβιετική Ένωση το είχε σχεδόν κατορθώσει με παρουσία στην Μέση Ανατολή και με τον μεγάλο της στόλο ο οποίος πριν την πτώση της συγκροτούσε μια από τις ισχυρότερες ναυτικές δυνάμεις). Μετά το Ψυχρό Πόλεμο, τα στρατηγικά παίγνια εντείνονται, παρά της προφητείες περί ανθόσπαρτου «παγκοσμιοποιημένου» πλανήτη. Βασικά, τέτοιες αυταπάτες βλέπουν όσοι κάνοντας λάθος ανάλυση καθιστούν τους εαυτούς τους αναλώσιμους. Οι κύριοι παίχτες των στρατηγικών παιγνίων συνεχίζουν να είναι περίπου οι ίδιοι με την ολοένα μεγαλύτερη πιθανότητα οι αναδυόμενες μεγάλες δυνάμεις να επιδιώξουν μερίδιο παρουσίας και πόρων. Εξ ου και η αντιπαλότητα θα εντείνεται ολοένα και περισσότερο. Στο περιφερειακό επίπεδο δεν υπάρχει αμφιβολία ότι, ιδιαίτερα μετά την επίθεση κατά του Ιράκ που βασικά το διέλυσε το 2003, το Ιράν, η Τουρκία και το Ισραήλ παραμένουν οι κύριοι παίχτες. Η δυνατότητα να αναπτυχθούν συσπειρώσεις μεταξύ Ισραήλ, Κύπρου και Ελλάδας βασικά εξουδετερώθηκε όταν για λόγους που δεν ερμηνεύονται εύκολα οι Έλληνες σύρθηκαν στο «κοινό ανακοινωθέν» που εάν οδηγηθεί στις λογικές του συνέπειες θα εντάξει την Κύπρο στον τουρκικό χώρο επιρροής καθιστώντας την Τουρκία κύριο στρατηγικό παίχτη στην Ανατολική Μεσόγειο. Η Σαουδική Αραβία είναι ένα ιδιόρρυθμο κράτος. Η οικονομική της ισχύς δεν αποκλείεται να την οδηγήσεις προς πυρηνικές κατευθύνσεις (ίσως σε συνεργασία με άλλα κράτη). Το Ιράν το οποίο μελλοντικά δυνατό να καταστεί πυρηνική δύναμη το θεωρεί αντίπαλο κράτος. Ταυτόχρονα αναπτύσσει πολλές δραστηριότητες, όπως για παράδειγμα στην Συρία. Το κείμενο που παρατίθεται πιο κάτω για την προσέγγιση Σαουδικής Αραβίας – Ιράν δείχνει την ρευστότητα των στρατηγικών στάσεων των περιφερειακών παιχτών, οι οποίοι, αναμφίβολα διασυνδέονται ποικιλότροπα με πλανητικούς στρατηγικούς παίχτες. Πολλοί για παράδειγμα διερωτήθηκαν για την στάση των ΗΠΑ όταν πριν λίγες μέρες στην Σαουδική Αραβία έγινε παρέλαση με πυραύλους που μπορούν να φέρουν πυρηνικά όπλα. Ποιας «ισλαμικής βόμβας», ερωτούμε ρητορικά, γνωρίζοντας την συζήτηση στην οποία κατά καιρούς πολλοί άλλοι εμπλέκονται, όπως η Τουρκία και το Πακιστάν. Το δεύτερο κείμενο που ακολουθεί το πρώτο είναι μια συνέντευξη του ίδιου ινστιτούτου όπου οι δύο σημαντικότεροι συντελεστές του, Robert Kaplan και George Friedman δίνει συνέντευξη ο ένας στον άλλο. Αφορά τη Συρία και το γεγονός ότι τελικά το καθεστώς Ασσάντ δείχνει προς στιγμή να επιβιώνει. Δεν θα προσθέσουμε περισσότερα καθότι έχουν αναρτηθεί στο παρελθόν και άλλα σχόλια, για παράδειγμα «Η σύρραξη στη Συρία και ο ανελέητος ηγεμονικός ανταγωνισμός ως καθοριστικός παράγων των περιφερειακών διενέξεων». Σημειώνουμε μόνο το γεγονός ότι και πάλι το Ισραήλ κατέχει κεντρική θέση και ότι από την σύντομη συνέντευξη γίνεται ολοφάνερο ότι συχνά οι μεγάλες δυνάμεις συμπεριφέρονται ερασιτεχνικά. Έτσι είναι ή μήπως πρόκειται για στρατηγικά παίγνια τα οποία ως γνωστό μπορούν να αλλάζουν κάθε στιγμή. Μάλλον το τελευταίο. Να πούμε μόνο ότι η Ελλάδα από κεντρικός συντελεστής που θα μπορούσε να είναι κατέστη απαθής θεατής και εξελίσσεται σε μεγάλο ασθενή που αρχίζοντας από τους Έλληνες της Κύπρου, την θέτουν, όπως γράφουν κάποιοι, πάνω στην κλίνη του Προκρούστη των στρατηγικών παιγνίων . Μελετώντας τις στρατηγικές εξελίξεις λάθος διάγνωση σημαίνει μεγάλες ζημιές ή και θάνατο. Η λάθος διάγνωση μπορεί να σημαίνει λάθος ανάλυση της διεθνούς πολιτικής και λάθος ανάγνωση του πως συμπεριφέρονται τα κράτη. Συναφώς, κανείς δεν έχει παρά να θυμηθεί τον μεγάλο Έλληνα στοχαστή Παναγιώτη Κονδύλη όταν έγραψε: «Η έσχατη πραγματικότητα συνίσταται από υπάρξεις, άτομα ή ομάδες που αγωνίζονται για την αυτοσυντήρησή τους και μαζί αναγκαστικά, για τη διεύρυνση της ισχύος τους. Γι’ αυτό συναντώνται ως φίλοι ή ως εχθροί και αλλάζουν φίλους και εχθρούς ανάλογα με τις ανάγκες του αγώνα για την αυτοσυντήρησή τους και τη διεύρυνση της ισχύος τους» (Ισχύς και απόφαση 1991).

Saudi Arabia Extends an Invitation to Iran

Summary

A Saudi minister’s purported invitation to have his Iranian counterpart visit Saudi Arabia could be a sign that Riyadh is acknowledging the need to talk directly with its longtime archrival. While the two countries see each other as their main competitor for influence in the region and are unlikely to come to any sort of accord, there is no shortage of matters on which the Iranians and the Saudis need to deal with one another, in particular regarding Syria and Lebanon. By opening up talks, Tehran and Riyadh could bring tensions down to a more manageable level.

Analysis

Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud al-Faisal on May 13 told a news conference in Riyadh that his Iranian counterpart, Javad Zarif, had been invited to visit the kingdom. Prince Saud was quoted as saying “any time that (Zarif) sees fit to come, we are willing to receive him. Iran is a neighbor, we have relations with them and we will negotiate with them, we will talk with them.” The Saudi foreign minister did not elaborate on when the invite was issued or whether the Iranians had formally responded.

This statement represents the first time the Saudis have said anything about Zarif — or any Iranian official — formally visiting the kingdom. For some time, only the Iranians had expressed interest in such a trip. Since Iranian President Hassan Rouhani’s government came to power and began negotiating with the United States on the nuclear issue, Tehran has shown an interest in reaching out to Riyadh as a way to prevent the Saudis from undermining the diplomatic process.

Aside from tactical-level issues such as the fate of the Lebanese presidency and the rebels evacuating the Syrian city of Homs, which backchannel talks between Riyadh and Tehran facilitated according to Stratfor sources, Saudi Arabia has not had an interest in engaging with Iran on a strategic level. The Saudis, who over the decades had grown accustomed to their main regional rival being a global pariah, are still coming to terms with the fact that the Iranians are on their way toward international rehabilitation. As a result, the Saudis have been trying to assess how they should deal with the Islamic republic. Additionally, from the Saudi point of view, there was no need to meet with anyone representing President Hassan Rouhani’s government, given Riyadh’s view that the real power was in the hands of the hardline clerical-military establishment, which had not changed its foreign policy attitude, especially as it applied to the countries’ mutual struggle for influence in the region.

Equally, there has been movement through another channel close to the government: Iran’s second-most influential cleric, former President Ayatollah Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, who has enjoyed a unique relationship with the Saudis throughout decades of mutual hostility. Recently, the Iranian ambassador to Riyadh met with Rafsanjani, where it was likely agreed upon that direct public engagement at the official diplomatic level would be pursued.

There are a number of reasons the Saudis would be willing to now formally engage with the Iranians. First, it is clear to Riyadh that the nuclear deal is likely to progress (even if slowly) and that Iran’s comeback on the world stage is inevitable, and it is not in Riyadh’s best interests to ignore it. Second, the Saudis believe that the Rouhani government is operating more or less in sync with the clerical establishment led by Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and resistance from within the security establishment, in particular the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, is in check. Third, there has been an unexpected convergence of interests between the two countries when it comes to Syria.

Saudi Arabia recently began a major campaign to counter transnational jihadist forces in Syria, such as the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant and Jabhat al-Nusra, and instead cultivate relatively moderate Salafist-jihadist forces. Although the Iranians are still wary of the Syrian Sunni rebels in general, Tehran sees this as a welcome step given the threat posed by transnational jihadist groups to Iranian regional interests. As far as the Saudis are concerned, their efforts toward regime change in Damascus have stalled, not only because of rogue jihadist fighters but also due to disinterest from the United States (and the West in general) for toppling the Syrian President Bashar al Assad’s regime.

The Saudis have been fighting on too many fronts simultaneously, which was unsustainable from their perspective. Consequently, the emerging regional landscape has pushed Riyadh to set foot on the diplomatic path in regard to Iran. This path however, does not lead to any rapprochement; rather, it will just bring down the tensions to manageable levels for the foreseeable future. For different reasons, neither side has an incentive to engage in any substantive negotiations and will not do so for quite some time.

Conversation: Al Assad Consolidates Power in Syria

Watch this video

Stratfor Founder and Chairman George Friedman and Chief Geopolitical Analyst Robert D. Kaplan discuss how Bashar al Assad has legitimized his authority over the course of the Syrian conflict.

Robert D. Kaplan: I’m Robert D. Kaplan, chief geopolitical analyst for Stratfor and I am here today with George Friedman, the founder and chairman of Stratfor. Recently, the Syrian regime seems to have taken full control of the Syrian city of Homs, the rebels have left under an agreement, is this a hinge point? Is this a turning point; does this mean that we are on the road to the Syrian regime of President Bashar al Assad winning the civil war, George?

George Friedman: This is not the turning point. The turning point came several years ago when something didn’t happen. The thing that didn’t happen was that the Syrian military didn’t split. And one of the things about revolutions is that until the military splits, changes sides, goes to war with each other, it is very difficult for a revolution to succeed. The Russian Revolution involved the army turning sides, the Iranian Revolution involved the entire security structure going to war with itself, in Romania the same thing. That never happened in Syria. For various reasons the Assad faction remained not only in control of the military, but the military remained effective. And that meant that the lightly armed guerrillas, rebels, simply couldn’t cope with the tanks, the planes, the helicopters that the regime had. So, it was Stratfor’s position back a while ago, Assad had really not so much won the war, but could not lose it. That meant the regime would survive and something else would replace it. They may not control all of Syria, but they would still be there. We used to think that it would be as a warlord, now it is something more than that.

Robert: Let me just run down the battlefield situation. The regime two years ago was in danger of losing Homs and had a very narrow umbilical cord of a supply line around the Homs area toward the Alawite area, connecting greater Damascus in the northwest. They have solidified that. They have solidified the core, however the rebels are still fighting in Aleppo — Aleppo is a contested city. And, even though the rebels have left the center of Homs, they are outside in bases and they control the northeast and the southeast, though one must say that those are the areas where not many people live in the first place, except along the Euphrates River Valley. So, while the Syrian regime is not on the point of winning the civil war, we can say that it is on the way certainly to consolidating the core, the demographic core of what constitutes Syria, with the exception so far of Aleppo. And in the process so far of doing that, George, Bashar al Assad has accomplished something else, something psychological. It was always thought that he didn’t earn his position as president, he was just his father’s son — of course the dictator Hafez al Assad, who ruled Syria from 1970 to 2000. But having people think that he was going to be toppled and not making a deal, fighting back, getting to the position where he is now, where he is more than a warlord, he is really gaining dominance over the Syrian core, he has made his bones so to speak. He has earned the right to be a mob-like dictator in Syria. And that gives him substantial legitimacy in the eyes of the people who count in a place like Syria.

George: One of the interesting things to bear in mind was that the international community, for all its rhetoric about nerve gas and everything else, really didn’t want Assad to fall. It wasn’t because they liked Assad — they didn’t — it was that the alternative had gotten scarier and scarier as the years went on. What began as a seemingly secular rising, Lebanese-style, against a government, increasingly contained a large faction of pro-al Qaeda, Jihadist forces. And you reached the point where the Russians were supporting Damascus and the Iranians are supporting Damascus. Even the Americans and the Israelis were, if not supporting them, certainly not prepared to put —

Robert: I believe the Israelis were terrified of what would replace Assad. Because Assad was more than the devil they knew, the Assad family, the Israelis had a de facto peace agreement of sorts since 1974.

George: Well, we remember that the Syrians invaded Lebanon the first time against the Palestine Liberation Organization in favor of the Christian factions, the Israelis were not unhappy seeing Syria dominating Lebanon and thereby guaranteeing, for example, that Hezbollah wouldn’t do much more than they would do. They had a pretty good understanding. They certainly would have rather seen him replaced by some sort of secular regime, but that wasn’t in the cards. Their choice was between Assad and the jihadists. And, without doing anything very much — the Israelis were not instrumental in this — they preferred Assad. That was one of the things that saved him, which is that the alternative, the rebels, became so unpalatable to so many countries — Iran, Russia, the United States — that no one was prepared to arm them in any way that could change.

Robert: For instance, the Obama administration looked around and said, “fine, you want us to arm the rebels?” because there was a lot of political pressure on the administration to do so. They said, “who do we arm? And how are we certain that the weapons are not going to fall into the wrong hands? And how are we certain that the political leaders who make their journey to the White House periodically, actually have any influence whatsoever on the ground in Syria?” So it was a great theoretical to arm the rebels, but when you actually got into the nitty-gritty of who you arm, and do they matter and will it fall into the wrong hands, it became less and less of an option.

George: It was very similar to Libya. It was all very well to talk about a repressive regime and its opponents, but at a certain point you have to ask who are the opponents? Who are the effective opponents? Who are those who are best organized? Who are the successors? When you change a regime, you take on a responsibility, not just a moral responsibility but a very practical responsibility. No one wanted to put in place in Syria a jihadist regime, because of Lebanon as well, because as Syria went, perhaps Lebanon would go in the same direction — perhaps Iraq.

Robert: Yes, and so I think what we have to look forward to is continued fighting, continued low-intensity war, but with the regime’s coherence and safety no longer challenged, or less and less challenged. George, that was fascinating. Thank you for joining us. I’m Robert D. Kaplan, thank you.